Why did the polls get the Caerphilly by-election wrong? They ignored the fact Reform is an English nationalist party

Plaid Cymru defeated Reform in Caerphilly, contrary to the findings of a poll. This discrepancy is due to inaccuracies in constituency polling and the influence of English identity on Reform. Pollsters should incorporate weighting for national identity to improve accuracy.

What you need to know

🔹 The by-election confounded polls, with Plaid beating Reform comfortably.

🔹 Constituency telephone polling proved unreliable compared with national surveys.

🔹 Welsh identity dominated in Caerphilly, limiting support for English-leaning Reform.

🔹 Pollsters should weigh national identity, while devolution gaps fuel English nationalism.

T he results of the Caerphilly Senedd by-election held on October 23 were certainly a shock to Labour and to the Conservatives, but they also cast doubt on the reliability of polling as well. It had for some time appeared that Reform was in the running to win the seat but it ended up trailing some way behind Plaid Cymru.

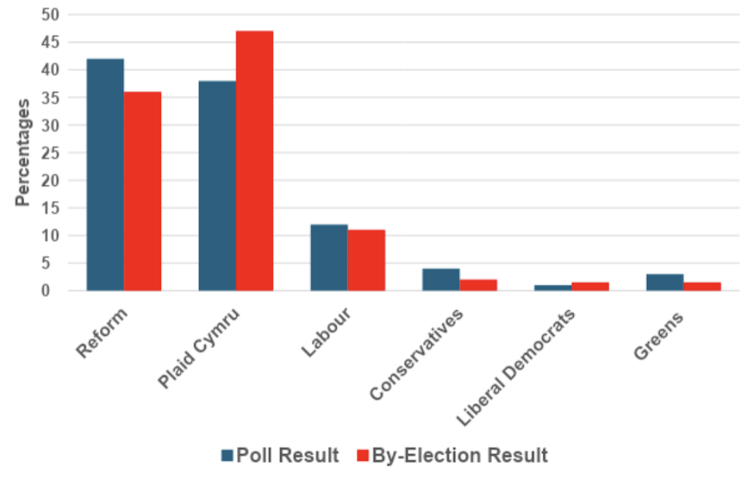

A Survation telephone poll published on October 16 suggested Plaid Cymru would come second with 38%, and the election would be won by Reform with 42%. The actual results after the October 23 vote were Plaid Cymru first on 47% and Reform second on 36%.

Labour obtained 12% in the poll and 11% in the election, which is fairly accurate. The Conservatives received 4% in the polling and got half of that with 2%. Similarly, the Greens also got half of their predicted share of 3% and the Liberal Democrats got 1.5% following a prediction of 1%.

Voting in Caerphilly – Poll vs Results:

So what went wrong? The small sample telephone poll in the constituency which Survation used does not have a good track record. Surprisingly, national polls are more likely to be accurate than constituency polls.

There are a number of reasons why this is true, chiefly that it is harder to get an accurate sample of respondents at the constituency level than it is nationally. This is particularly true of telephone polls, where the great majority of people approached will not respond.

But there is another important reason why Reform did worse than expected in the by-election and it relates to national identity. The 2021 census asked questions about people’s national identities – that is, did they feel British, English, Welsh, Scottish, and so on.

Overall, 90% of the population (53.8 million people) in England and Wales identified with at least one UK national identity. This makes it possible to investigate identities at the constituency level.

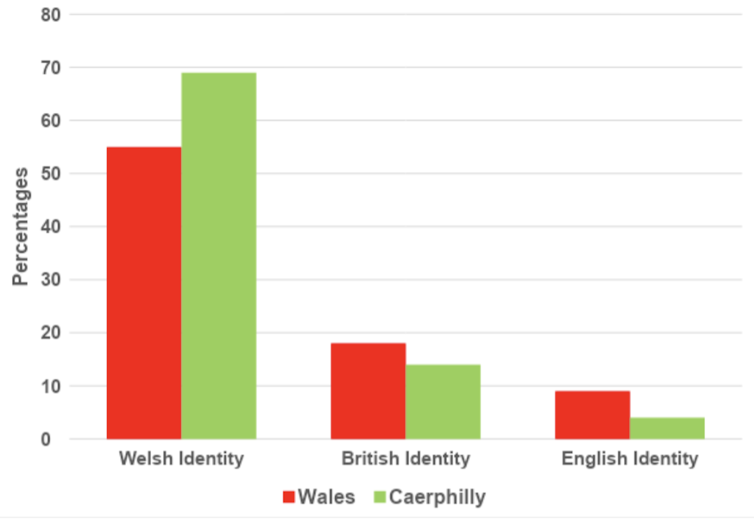

Some 55% of the population in Wales described themselves as Welsh in the census, but in Caerphilly it was 69% – a far higher figure. Equally, 18% described themselves as British in Wales but in Caerphilly it was 14%. Finally, 9% of the Welsh population described themselves as English, but only 4% of the population in Caerphilly did so.

Census National Identity Data, Comparing Wales and Caerphilly:

It’s also revealing to compare the constituency and the rest of Wales when it comes to voting in the general election of 2024. Plaid took just under 15% of the vote in Wales but it took 21% in Caerphilly. Reform took 17% in Wales and 20% in Caerphilly.

This is why many thought that Reform would win the by-election. So why did Plaid get 11% more of the vote share than Reform in the by-election?

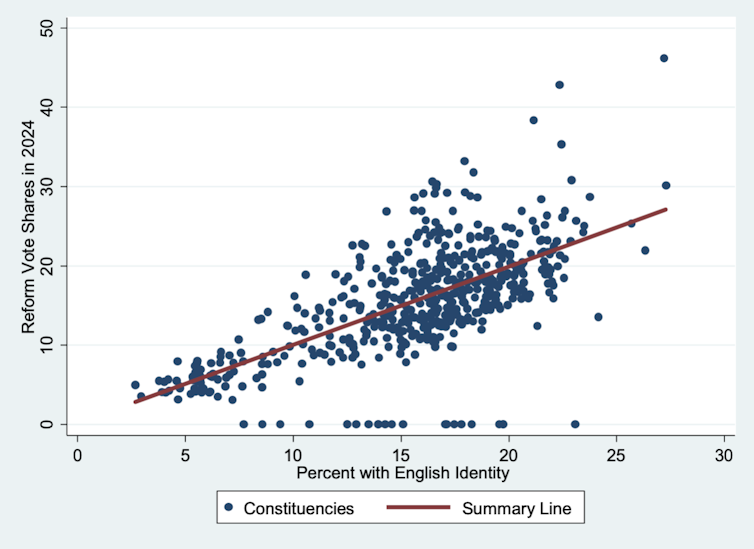

The main reason is that Reform is fundamentally an English nationalist party, as the chart below reveals.

There is a very strong correlation between English identity in the census and voting Reform across the 543 constituencies in England. The more people think of themselves as English rather than British or something else, the more they were likely to vote Reform in the 2024 election.

English Identity and Reform Voting in 2024:

Because English identity is low in Caerphilly, even by Welsh standards, Reform struggled to get the support it would have received in a comparable constituency containing a lot more English identifiers. It did well in the general election because this was focused on the entire UK, but when the focus is on Wales in a by-election, English identity is a problem for the party.

More generally Reform will face difficulties in the future winning seats in both Wales and Scotland, since English identifiers in these countries are few and far between.

This is going to be an issue in the Welsh Senedd elections and also the Scottish Parliamentary elections next year, since Plaid Cymru and the SNP are likely to be more successful against an unpopular Labour party in their respective countries than is Reform.

For next year’s local government and devolved parliamentary elections, there is something the pollsters can do to correct for the national identity effects.

All pollsters weight their data, that is, they attach more importance to some respondents than others in order to get an unbiased sample. They should weight for national identity using the census data and this will help to make the estimates more accurate.

Reform is in part a product of the incomplete devolution experiment introduced by Tony Blair’s government in the 1990s and 2000s. This exercise provided a powerful parliament for Scotland and a less powerful but important parliament for Wales.

The missing element was a parliament for England. It was thought at the time that this was unnecessary since the Westminster parliament would take care of English issues, but with English nationalism on the rise, it may well be time to reconsider this arrangement.

GOING FURTHER